KANSAS CITY, Mo. – The Chiefs officially started the offseason workout program on Monday, but whether the team is 100 percent strength at the tight end position remains to be seen.

Aug 9, 2013; New Orleans, LA, USA; Kansas City Chiefs tight end Travis Kelce (87) against the New Orleans Saints during a preseason game at the Mercedes-Benz Superdome. Credit: Derick E. Hingle-USA TODAY Sports

Chiefs coach Andy Reid said Travis Kelce, who missed his rookie season after undergoing mircofracture knee surgery in early October 2013, is “progressing well and doing everything” when it comes to the first phase of the offseason program.

The first phase includes voluntary workouts in the form of weight lifting and running with strength and conditioning coaches, and classroom sessions with members of the coaching staff.

When asked to clarify if Kelce was medically cleared, Reid didn’t offer a definitive response.

“He’s right there,” Reid said. “How about I say it that way? He can do what we’re doing right now.”

Still, if a player hasn’t been medically cleared in April from an early October microfracture knee surgery wouldn’t be cause for alarm, according to Dr. Jeff Dugas of the renowned Andrews Sports Medicine & Orthopaedic Center in Birmingham, Ala.

While Dugas didn’t personally evaluate Kelce, he offered an opinion during a phone interview based on his area of expertise with orthopedic sports injuries.

“If I was reading the newspaper and I’m a Chiefs fan, that wouldn’t disturb me knowing what I know about it,” Dugas said. “There are three more months until he needs to be full-go.”

Of course, hearing of microfracture knee surgery could cause a layman to cringe.

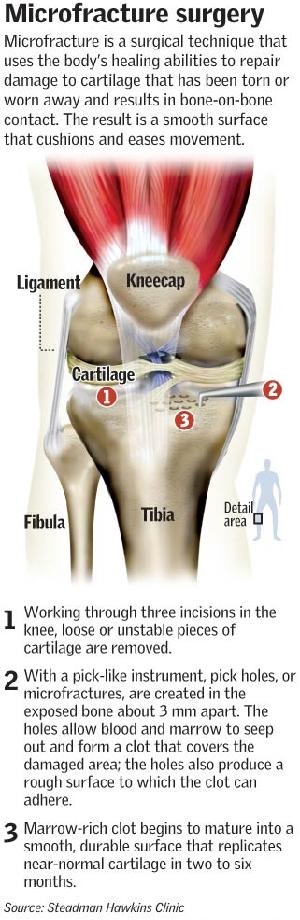

The process involves identifying the cartilaginous defect, and then inserting multiple small holes in the bone close to the defect 3 to 4 millimeters apart. Doing so stimulates the bone marrow to produce cartilage or cartilage-like tissue in an attempt to heal itself.

Notable NFL players to reportedly have the surgery in recent years include tight end Kellen Winslow Jr. (2007), running backs Maurice Jone-Drew (2011) and Reggie Bush (2008), and wide receiver Marques Colston (2009, 2011).

In the NBA, Jason Kidd, Chris Webber, Anfernee Hardaway, Tracy McGrady, Greg Oden and Amar’e Stoudemire are among players to have undergone microfrature surgery.

Overall results are mixed, but Dugas said the microfracture procedure is an “evolving science,” adding there are factors to consider.

“The success rate of microfracture is highly dependent on so many things,” Dugas said. “Age, location, size, physical demand of the patient and overall health of the patient all contribute to the success rate.

“The size of the defect is obviously one of the more important things, so every defect that gets microfractured will be in some way different. They’re like footprints. If you’re talking about a small defect, say 1 square centimeter, the success rate for that will be much higher than a defect that is 6 square centimeters.”

When it comes to recovery, the defect location, whether in a weight-bearing or non-weight-bearing area, plays a role.

In Kelce’s situation, the tight end experienced issues getting in and out of his stance, but could run without pain. Chiefs head athletic trainer Rick Burkholder said on Oct. 9, 2013 that Kelce’s defect was identified in the articular cartilage in a non-weight-bearing area.

That information proved important to Dugas’ forecast for a recovery timetable.

“I would expect that with microfracture surgery of the knee, most NFL athletes would take at least six months to return to normal levels of performance and competition,” Dugas said. “But again, obviously the smaller the defect, the less you’re asking of the body. The bigger the defect, the more you’re asking.”

A final consideration with recovery surrounds a patient’s history.

Former NFL running backs Terrell Davis and Stephen Davis, both of whom had a history of knee injuries, were arguably never the same player after a microfracture procedure.

“If the cartilage defect is isolated and there is no other pathology in the knee, the success rate of microfracture surgery is very high in terms of getting a healthy tissue to grow,” Dugas said. “If there is associated meniscal damage or widespread arthritis, the success rate of microfracture surgery decreases. Also, knee stability plays an important role. If the knee isn’t stable, like in the ACL deficient knee, the success rate of microfracture surgery goes down.”

Kelce doesn’t have a history with knee injuries, and his known health concerns coming out of the University of Cincinnati surrounded shoulder and sports hernia injuries.

Nevertheless, getting him back from microfracture surgery and ready for the upcoming season is essential to bolster the Chiefs tight end corps in Reid’s version of the West Coast offense.

[Related: Healthy tight ends key to Chiefs offense]

Despite not playing last season, Kelce had the benefit of staying in Kansas City during his recuperation. Being around the team and learning the complex offense before the offseason provided an advantage.

“That part, that was a big thing,” Reid said of Kelce’s ability to attend regular season team meetings following surgery. “Once the season was over, then you’re done until today (Monday) with the football part.”

Former NFL tight end Luther Broughton, who played two seasons for Reid in Philadelphia (1999-2000), agreed with his former head coach.

“The one big challenge for him is his knee,” Broughton said of Kelce in a phone interview. “Let’s be honest, microfracture, that’s a tough one. The good thing about it is he’s been there a year; it’s not like he’s coming out of college. He’s been studying and that’s a humongous head start.”

Former three-time Pro Bowl Eagles tight end Chad Lewis echoed Reid and Broughton.

“Since he’s been there a year, then it will be very important for him to know his position,” Lewis said in a phone interview. “He’s been in meetings, he needs to know where to line up and that’s just the basics.”

In the meantime, in the event Kelce isn’t ready to return to unlimited physical activity shouldn’t hurt the underlying objective from a professional team’s point of view when it comes to microfracture surgery.

And the timing of an athlete to undergo that procedure in early October should keep a player on track barring a setback.

“The goal for that athlete and that team is for him to be ready to play in August-September,” Dugas said. “If he doesn’t perform in April or May, that doesn’t necessarily mean he won’t be ready to perform in August-September.”